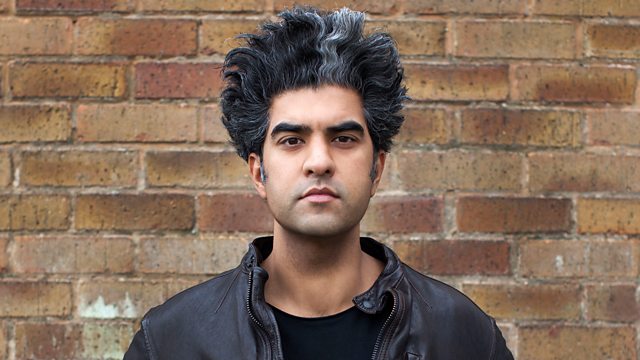

Mahtab Hussain: “The question I asked myself: what does it mean to be a British Muslim male today?”

CLOVE What were your intentions when embarking on the project?

MAHTAB HUSSAIN The question I asked myself was, what does it mean to be a British Muslim male today? There’s this idea that the Asian male has to be the big man, the tough man, the hard man, who has power, money and respect. If they are not, they’re considered weak. I was questioned about my sexuality on many occasions and I learned quickly what being a man in the Asian community meant. Not all men behave like that, but all are aware of that pressure.

What it means to be a man has been redefined over the past 30 years, and, like others, the Muslim male is having to figure out a new role. The working class man has gone through the biggest change since the 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher started breaking down community – livelihoods have been destroyed, unions dismantled, and the working class man has lost a core part of his identity. The masculine role has become more complex and layered and, in that context, the ‘man’s man’ is struggling.

CLOVE How did you decide who to photograph?

MH There had to be something that drew me to a person – how they held themselves, their sense of style or individuality. When that happened, I would stop them and try to engage. On the whole it was great, but I had to overcome difficulties: at one point, I walked and cycled the streets for more than a week without connecting with anyone. People were not interested or they believed nothing was going to come of my work – that I was wasting my time and that I couldn’t do anything to stop all the hatred they faced. There was also a lot of paranoia: I was accused of working for the government, FBI, MI5 or MI6.

When people started to see the work, it changed. I also moved to digital photography so they could see what I was making. When I began sharing the work with people I respected in my community, one father told me that he realised he needed to be a better father to his sons. I felt it was important to include the voices of the men I had met who wanted to talk about their problems in the book. The voiceless need to be heard.

CLOVE How did this project differ from your previous one where you photographed Muslim women, Honest With You?

MH That was my master’s project, which I am still developing. I felt the women were in a much better place when it came to feelings of displacement – they had a greater sense of balance with their religious identity, their sense of self and their feelings towards wider society. The women were articulate, and focused on careers and education in ways that left the men behind. They’re attempting to throw off the chains of sexual discrimination in a community that often insists on maintaining certain ways of life in the face of western modernity.

CLOVE What do you hope to achieve through these works?

MH I would like You Get Me? to begin to articulate how damaging it must be to be born at a time when negative Muslim news fills our channels. I often think about how the youth today cope with the pressures of the media and exist in a political environment they feel is weighted against them. It must be so difficult to be born into a world that tells you that you do not belong, that inherently you are a problem and danger. 9/11 happened in 2001: that was 17 years ago – so you have young people in their early 20s who have only know hate and resentment. I also rarely see us on TV, in magazines or on billboards. The potent ‘us vs Muslims’ propaganda has allowed this bias to become acceptable. Muslims are generally assumed to be the instigators of violence – hardly ever the victim. This has dehumanised the community, while also encouraging a fear of itself. I want to humanise their experiences and show what they are going through. It is important that we recognise that each of the men in my series has their own unique story of boyhood and manhood.

Mahtab Hussain’s You Get Me? is available to order through Mack Books