Decoding the Enigmatic Ayurvedic Man

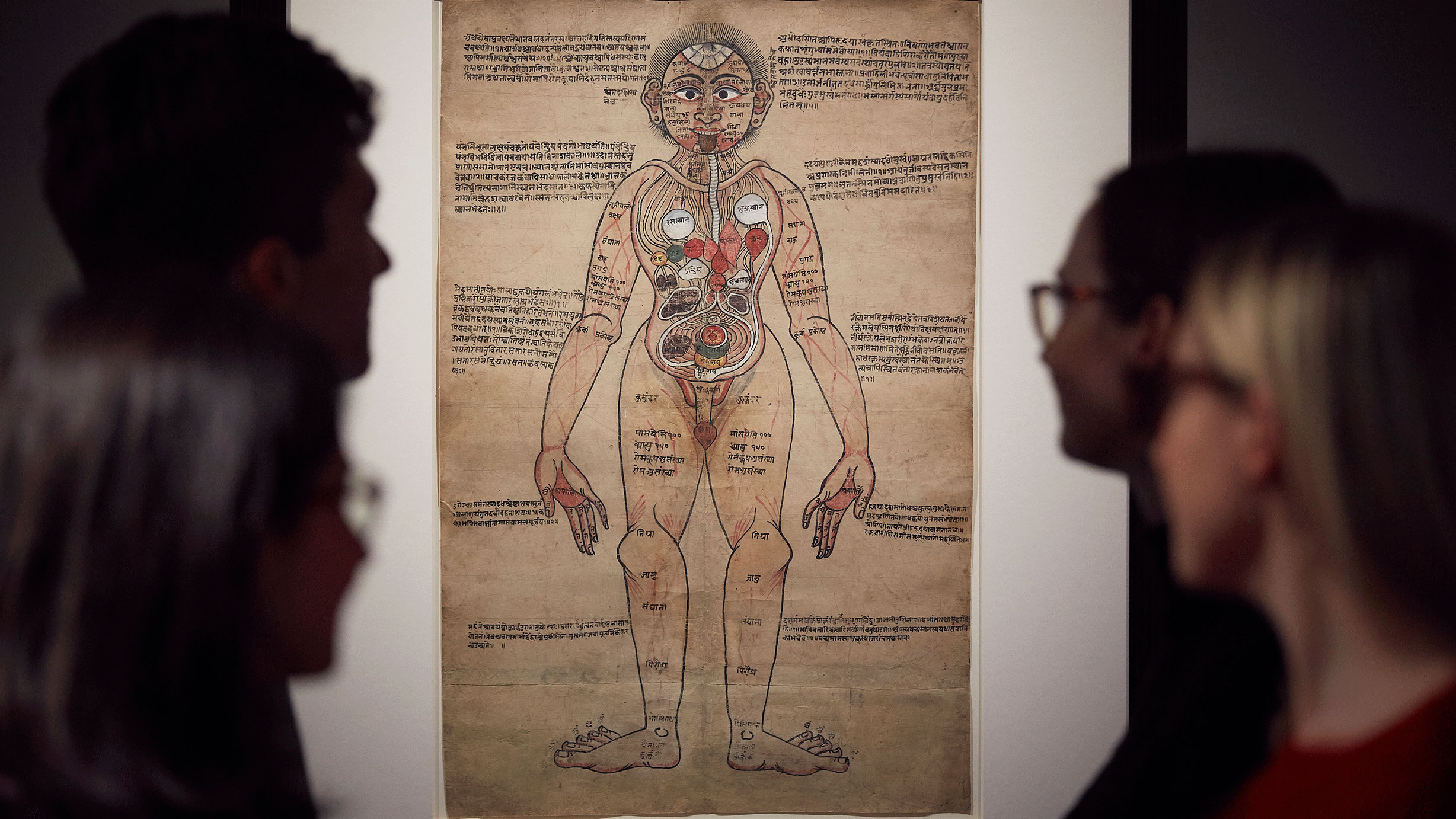

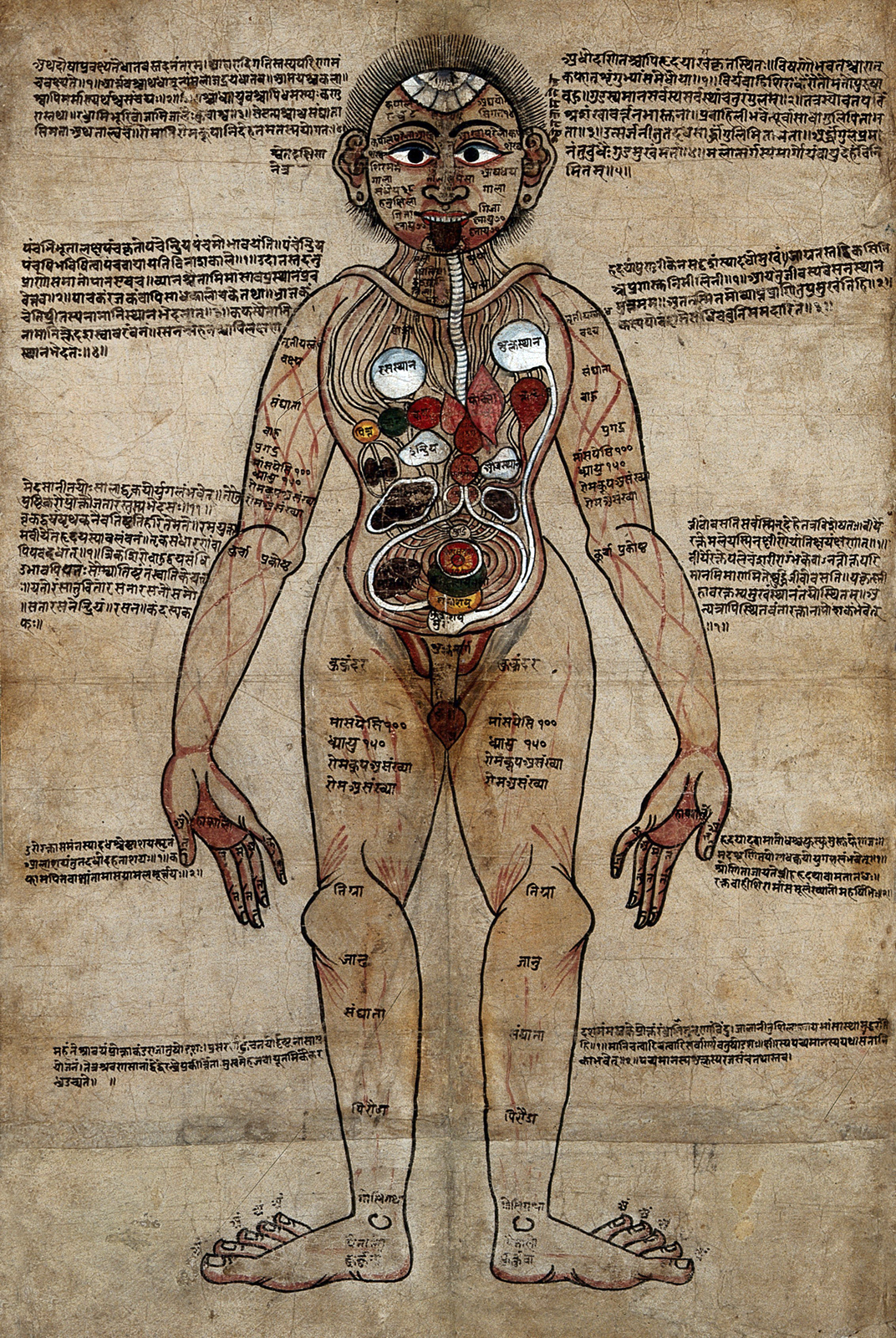

Behold! A manuscript of mesmerizing intrigue—a visual symphony of the male form, adorned with Sanskrit excerpts from the 17th-century Ayurvedic text ‘Bhāvaprakāśa’ by Bhāvamiśra. Still revered in Ayurvedic medical colleges today, this work is a timeless bridge connecting past wisdom with present practices.

Who, you might wonder, was the intended beholder of such an enigmatic creation? Dominik Wujastyk, having delved deep into its mysteries, hints that its pristine condition and method of creation offer tantalizing clues.

Imagine this: an Ayurvedic physician, Tibetan artists, and a calligrapher, all converging in the vibrant heart of Kathmandu, Nepal, to birth this masterpiece. The painting, intriguingly flat and unblemished by the ravages of time, suggests it was meant for display, perhaps in the hallowed halls of a royal physician or a sacred space for teaching. The vivid colors, unmarred by daylight, whisper of careful preservation.

Open Eyes Suggest Life

One question haunts the mind: was the artist portraying a lifeless body, or a living, breathing human? The open eyes and the figure’s style evoke the ‘body maps’ of Tibetan medicine, used to denote bloodletting and moxibustion points—relevant only to the living. Yet, the anatomical precision speaks of dissection, of studying the dead.

Illustrations in Sanskrit tradition are rarities, but Nepali and Tibetan texts are more generous with visual aids. This striking image at the manuscript’s core marks a unique interpretation of Ayurveda, blending traditions in a dance of artistic and medical brilliance.

A Written Reminder

For those unversed in Sanskrit, the manuscript’s visual allure is but a fraction of its richness. Encircling the painting are texts from the third chapter of ‘Bhāvaprakāśa’. Dominik Wujastyk’s meticulous transcriptions and translations reveal a web of meaning, obscured by the original’s myriad errors—20 or more per passage!

Kapla (phlegm) is poetically depicted as “moistener, dripper, taster, oiler, and gluer”. The calligrapher’s unfamiliarity with Sanskrit likely necessitated close collaboration with the physician. Nine texts in total, with labels in Bhasa, a vernacular offshoot of Sanskrit, adorn the body’s various parts. This painting was likely a mnemonic tool for its owner, with texts in verse aiding memory, though their painted form defies traditional structure.

The Brushes, Ropes, and Grooves of the Body

Even in translation, the texts’ language sings with poetic beauty. ‘Text A’ surveys the body’s landscape, describing:

“…the orifices and mass of tubes with nets, and the brushes and ropes, the grooves too, and the junctions and aggregate bones, the seams and also the skin, the hairs and pores. The body is thought to be made of these.”

Other texts, like ‘Text B’, provide detailed anatomical descriptions, even of the testicles, while ‘Text C’ delves into Ayurveda’s theoretical underpinnings, the triad of vata, pita, and kapla. Each quality’s functions shift with its bodily location—Kapla (phlegm) again described as “moistener, dripper, taster, oiler, and gluer”.

As in ancient Greek medicine, Ayurvedic diseases arise from imbalances in these qualities.

Ayurvedic medicine, a millennium-spanning tapestry of South Asian medical practices, lives on robustly. This manuscript, a testament to collaboration and interpretation, bridges the gap between ancient wisdom and contemporary practice, a relic of enduring beauty and profound knowledge.