Echoes of War: An Artistic Vision of the Civil War

Imagine walking into a labyrinth of art, where every corner whispers tales of a tormented past, a relentless echo of war. Last years Colomboscope was held with the intriguing title ‘Language is Migrant’, it delves into the profound effects of Sri Lanka’s civil war, seen through the vivid imagination of young artists from the north and east of the country. Their creations, sprawled across multiple venues in the city, morph from drawings and paintings to sculptures, embroidery, videos, documentaries, photographs, installations, plays, readings, poetry, and discussions. It’s an all-encompassing sensory assault, pulling you into their world of bombardment, siege, and ceaseless displacement.

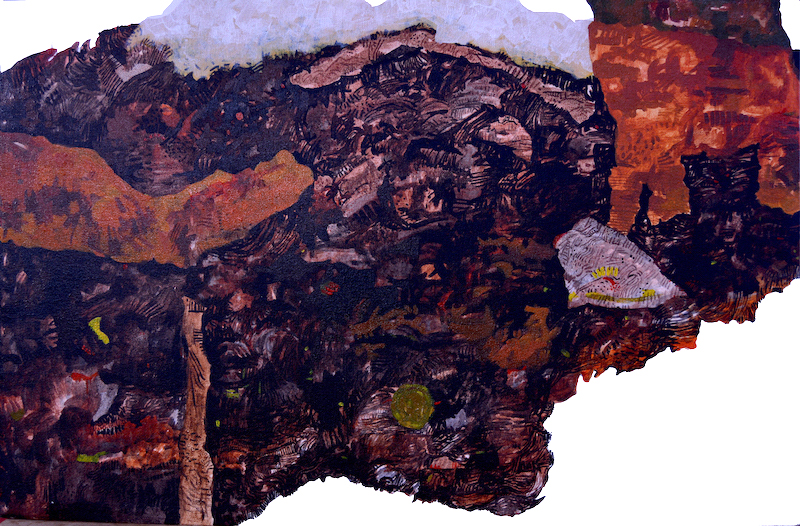

Suntharam Anojan’s pieces, drenched in the earthy hues of Vanni—browns, ochres, and greens—reflect a land scarred by war. His portrayal is raw and unfiltered: burnt forests, remnants of explosives, flattened homes. It’s a landscape that’s seen too much.

At Colomboscope, Anojan unveils a colossal 20-foot-long canvas that meanders through the space, a serpentine testament to mass destruction. This undulating artwork is not just about physical ruins but the essence of living without permanence, moving from one precarious shelter to another.

What experiences in your life influence your art?

I was born in Mullaitivu in 1991. Since I was ten, I lived away from family for studies. The war-torn landscape, the people, the animals, even the plants—they haunted my thoughts. Visiting Mullivaikkal, I saw a land disfigured by violence. It mirrored my inner trauma. It felt disabled, and so did I. From this, I began to paint the concept of disability—not just the physical but the psychological wounds inflicted by war. The greenery, to me, was a ghost of the bodies burnt and buried. I paint black landscapes; they are my soul’s reflection. Art, for me, is a balm for these wounds.

What do you want people to learn from your art?

When I create, I don’t think about the audience. My art is an experiment, an extension of my life, an expression of my mental state. I draw for myself, paint for my soul. Through distorted forms and colors, I share my stories. I am fluent in art, my true language. It’s powerful, political. I don’t aim for reconciliation; I aim to share my truth.

In stark contrast, Vinoja Tharmalingam’s delicate embroidery tells harrowing stories of loss and shattered lives. Based between Kilinochchi and Batticaloa, Vinoja’s work explores the themes of disability and war widows. Her pieces, with dots, cloth patches, burns, and lines, depict a community still ensnared by the remnants of war—landmines that dot the landscape, the constant threat of hidden dangers.

Her embroidery becomes a metaphor for healing and mending. Despite the war’s end, the scars remain, etched into the very fabric of everyday life. Her works resonate with the transient lives of those who have known only migration, from home to bunker to refugee camp.

What did people in Mullivaikkal experience during the last days of the war?

During those final days, my family and I were in Mullivaikkal. From January to May 2009, we lived in tents, bunkers our only shield. There was no food, no medicine. Fear was a constant companion. Bombs exploded everywhere, the air thick with the stench of blood and decay. The land itself seemed to erupt, decomposing under the weight of death and destruction.

What experiences in your life influence your art?

My art is born from my experiences and the community around me. When I was six, my family fled to India. One evening, we heard cries—a boat had capsized, and twenty-five people drowned. That memory haunts me. When we returned to Sri Lanka, the war raged on. Those painful memories fuel my art, capturing the essence of living through hell.

Do you think art has a healing aspect?

Absolutely. Art bridges the mind and body, sparking innovation and healing. When I stitch or draw, I channel subconscious thoughts into physical form. It’s a therapeutic process, revealing hidden truths and buried stories.

What do you want people to learn from your art?

My art delves into conflict, memories, trauma, and loss. Through my work, people can learn that these thoughts carry untold truths and stories, events that remain unwritten and silent.